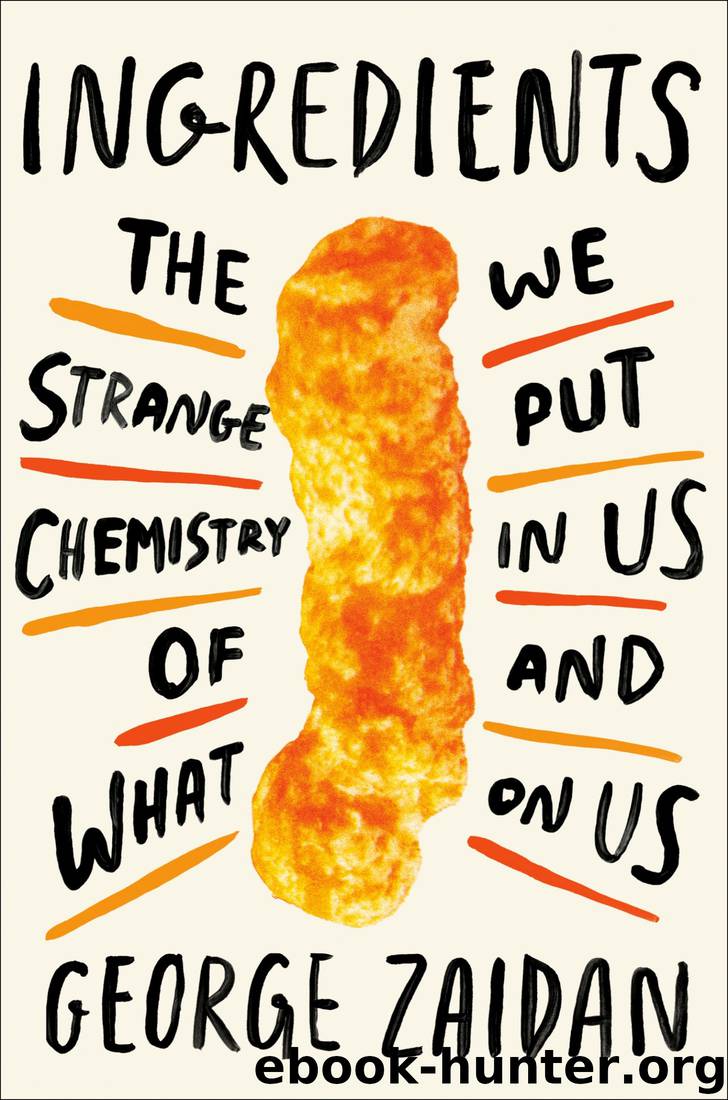

Ingredients by George Zaidan

Author:George Zaidan [Zaidan, George]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Penguin Publishing Group

Published: 2020-04-14T00:00:00+00:00

All of these headlines are from before the year 2000. After Y2K, the pace of their publication accelerated. In a highly nonscientific mini-experiment, I searched Lexis Nexis for news articles between 2000 and 2019 in health sections of newspapers and wire services that had “coffee,” “risk,” and “increase” or “decrease” in the story; I got 2,475 hits for “increase” and 615 hits for “decrease.” Even if you assume that half of these results are not relevant and half of the remaining ones cover the same underlying science, that’s still 600-plus stories telling you coffee increases your risk of something and 150-plus stories telling you it decreases your risk of something.

My initial reaction to this was:

Are

You

Kidding

Me

This

Is

A

National

Embarrassment.

Come on, science! It’s a simple question: Is coffee good or bad? Should I drink it? Look, I know research is hard, but isn’t MORE THAN TWENTY YEARS enough time to come up with an answer?

Coffee is far from the only food that generates conflicting headlines. In 2016, two scientists at Stanford Medical School pulled The Boston Cooking-School Cook Book off the shelf and chose fifty ingredients at random, then trawled the literature for studies that attempted to link each ingredient to cancer. (These were not obscure ingredients like sweat from the udder of a lactating goat milked during a full moon. These were salt-of-the-earth ingredients like eggs, bread, butter, lemon, carrot, milk, bacon, and rum.) After excluding ingredients for which there were fewer than ten studies, there were twenty ingredients left. Of those twenty, only four had results that entirely agreed with each other. The rest—in other words, 80 percent of the ingredients—had studies with at least one conflicting result. Some, like wine, potatoes, milk, eggs, corn, cheese, butter, and, yep, coffee, had multiple conflicting results. And that’s how you end up with what statistician and science communicator Regina Nuzzo calls “whiplash news.”

We get pissed at politicians when they change their mind once; how the hell can science change its mind about a single food dozens of times?

Ladies and gents, I’d like to officially welcome you to—angelic choir sound effect—nutritional epidemiology. Nutritional epidemiology is the study of what foods are going to send you to an early grave, and the source of most headlines you read about food and health.

Nutritional epidemiology is mostly based on long-term prospective cohort studies. We’ve talked about these studies before: they’re similar to the ones done in the 1950s on smoking and lung cancer. You enroll a bunch of people, ask them lots of questions about how they live their lives, follow them over a long period of time, and record what diseases they get. What pops out of these studies is an association (also called a correlation, but I’ll stick with the word association throughout this book). The studies on smoking found an association between heavy smoking and a 1,000-plus percent increased risk of getting lung cancer. A typical nutritional epidemiology study might find an association between, for example, drinking about two cups of coffee per day and a 30 percent increase in risk of breaking your hip if you fall.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Craft Beer for the Homebrewer by Michael Agnew(18218)

Marijuana Grower's Handbook by Ed Rosenthal(3659)

Barkskins by Annie Proulx(3346)

Project Animal Farm: An Accidental Journey into the Secret World of Farming and the Truth About Our Food by Sonia Faruqi(3207)

The Plant Messiah by Carlos Magdalena(2913)

Red Famine: Stalin's War on Ukraine by Anne Applebaum(2908)

0041152001443424520 .pdf by Unknown(2832)

Organic Mushroom Farming and Mycoremediation by Tradd Cotter(2672)

In the Woods by Tana French(2575)

Beer is proof God loves us by Charles W. Bamforth(2434)

7-14 Days by Noah Waters(2398)

Borders by unknow(2295)

Reservoir 13 by Jon McGregor(2282)

Between Two Fires by Christopher Buehlman(2281)

Meathooked by Marta Zaraska(2251)

The Art of Making Gelato by Morgan Morano(2243)

Birds, Beasts and Relatives by Gerald Durrell(2202)

The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: Powerful Lessons in Personal Change (25th Anniversary Edition) by Covey Stephen R(2178)

The Lean Farm Guide to Growing Vegetables: More In-Depth Lean Techniques for Efficient Organic Production by Ben Hartman(2122)